Ziffer House Archive: Documentation and Research Center of Israeli Visual Arts

|

Beit Ziffer Archive is open appointment only:by telphone or email. The Weiner Library sponsored by Caroline & Joseph S. Gruss (near the Sourasky Library), First Floor

Bait Ziffer Archive is open to students, lecturers, researchers, art critics and curators as well as to artists and followers of Israeli art. In addition to the study facilities in Bait Ziffer Archive, visitors may also photocopy or photograph the various documents and reproductions. |

|

Ziffer House Archive

University as a documentation and research center of Israeli art. In 1993, after long restoration works highly respecting the original plans of the building, the Ziffer House opened its gates for regular activity.

The ground floor, formerly the artist's studio, houses a permanent representative exhibition of Ziffer's work as well as documentary material on his life and work. This large hall is also used for lectures and assemblies. The mezzanine floor houses the offices and archives, and on the upper floor are the library, study and reading room and a small cafeteria.

The center provides services to students, lecturers, researchers, curators, artists and art critics in Israel and from abroad. Its library is also accessible to high school and art school students and to individuals interested in various aspects of Israeli painting and sculpture.

The Documentation Center is a scientific oriented center under the supervision of the Art History Department of the Tel-Aviv University. Unlike other documentation and archive centers, this center does not deal only with the collection and preservation of documentary material but rather initiates fieldwork and promotes research in a scientific and methodical manner in view of further extensive research.

The subjects covered at the center include: the history of Israeli Visual arts (painting, sculpture, photography, installation, video art etc.) from the turn of the century until the present day; the work of individual artists; the activities of groups and societies of artists as well as artists colonies and centers (Safed, Ein-Hod, etc.) One man shows and group exhibitions in Israel and abroad, art schools, museums, galleries and private collections as well as general issues such as relations of artists and their societies with the establishment in its various manifestations, involvement of artists in society and the state; ideological and aesthetic questions, history of art criticism in Israel, relationship with other fields of art, historical, regional and international influences on Israeli art, etc. Besides, the Ziffer House handles bequests from deceased artists at the request and with the support of their families. This includes photographing and recording the works in a card index, as preparation for a catalogue raisoné; arrangement of documents (letters, manuscripts, newspaper clippings) and filing them in the artist's file; recording the books, pictures and/or reproductions of the work of other artists that were found in the artist's studio and home. This detailed work is carried out by graduate and undergraduate students. The students are guided and supervised by the center's academic staff.

The bequest of the sculptor Moshe Ziffer, and the fund created by Mr. John Porter in order to provide the basic charges of the house, helped create the appropriate objective conditions for advancing and developing the scientific documentation of the plastic arts in Israel. Such documentation is essential for deepening and expanding serious research, and only the involvement of an academic institution can insure that such research is conducted at a level worthy of its name. In order for the center to be able to fulfill its intended function, it requires resources that the university, in its present economic straits, is unable to provide. The future activities of Ziffer House, as well as that of the scientific oriented research in Israeli art, depends to a large extent on the generosity of supporters and donors both in Israel and abroad.

Ziffer's House in Tel-Aviv serves as the central archive and research source of Israeli plastic art. The first floor, in what was Ziffer's studio, now houses a retrospective exhibit of his works; on the middle floor are the office and archives; and the top floor features the library and study area. The data files and research material have been organized under the supervision of Prof. Gila Ballas, who also acts as Director of Bait Ziffer in coordination with the Department of Art History of Tel-Aviv University. Bait Ziffer is open to students, lecturers, researchers, art critics and curators as well as to artists and followers of Israeli art. In addition to the study facilities in Bait Ziffer, visitors may also photocopy or photograph the various documents and reproductions.

Gila Ballas / Moshe Ziffer The Man and the Artist

"His work is simple and noble as the man who created"

Prof. Albert Einstein

Moshe Ziffer was born on April 24, 1902 in the town of Przemysl, Galicia, and died in Tel- Aviv on April 9,1989. His father was an artistically gifted self- taught master builder and plasterer. Ziffer studied in a Polish gymnasium but at home was raised in the spirit of Zionism. He began to study Hebrew at the age of six, and was a member of the Zionist Youth Movement Ha'Shomer Ha'tzair. He was sent by the Pioneers' organization for training in preparation for Aliya (emigration to Eretz Israel) for which purpose he studied carpentry for three months. At the age of 17 he left home. Following a long journey through Germany, Austria and Trieste, he finally arrived in Jaffa-Tel- Aviv. For about three years he worked at various jobs in Kastina, including construction of the Haifa - Gedda road. In November 1922 he joined Kibbutz Beit Alpha where he worked at a variety of jobs, mainly construction carpentry. The turning point in his life occurred in 1924, when he fell ill and was bedridden for a long period. It was then that he began reading, in German, Mereszkowski' s book on Leonardo da Vinci, which inspired him to start carving figures from the blocks of wood available in the kibbutz workshop. In October, 1924, after a brief stay in Jerusalem (where he worked as an assistant to the sculptor Melnikov) he left for Vienna to convalesce and began to study sculpture at the Kunstgewerbe Schule ( the School of Arts and Crafts) under the sculptor Steinhof. This fortunate choice was to influence his future as a sculptor.

Prior to World War I, Steinhof had spent in Paris several years and had close connections with local artists who belonged to the avant garde movement. A photograph of one of his sculptures in the French journal "L'Art Vivant" shows a great resemblance to the works of Archipenko and Gargallo. As a teacher Steinhof gave the highest priority to the developing of his students, opposing the conventional academic methods of imitation and copying, and elaborating instead innovative and modern methods. Under his guidance the students began by working upon "abstract" basic forms, which to his way of thinking were "the only ones that permitted an elementary perception of intrinsic laws". After this, and in order to prevent an over enthusiasm for abstraction, they continued by learning to make vases, for the vase form both excels in absolute purity and has a meaning that is universally understood. In this way, the students attained technical skills and high standards of execution while learning to ignore minor details, and look instead for the essential lines and observe the play of light on form. In the second phase of their studies the students modeled geometric forms in plaster and engaged in constructing architectural models while paying special attention to the harmony of cubes. The third phase was one of refinement and emotional expressiveness and included the study of colors through designing rugs and mosaics. It was only in this latter phase that the student finally reached the moment, which for Steinhof was the most critical: that of a return to nature. It was only now that they were ready to sculpt the human figure without the aid of a model.

Steinhof's teaching method is most important to an understanding of Ziffer's work. It was this method which established the source of the simplicity and purity of line in his figurative sculptures, from which we can follow his development to abstract sculpture in the mid-1950s as a natural and obvious progression, rather than a mere following of fashion.

During his studies in Vienna Ziffer modeled many large clay sculptures (using the vertebrae method) as well as works in stone and wood. He revealed a complete mastering of all these techniques, and when he exhibited 23 of his sculptures at the Holbein Gallery (October 1928) his work was widely acclaimed. About a year earlier (in the spring of 1927) Ziffer had travelled to Paris with Steinhof and accompanied him on his visits to the studios of SteinhofÕs friends Brancusi and Gargallo. His meeting with Gargallo left a deep impression on Ziffer. He felt that Gargallo's sculptures contained an element, which was missing in his own: a very deep knowledge of nature; that is to say, of the human body. Consequently, despite the great success of his exhibition, Ziffer decided to travel to Berlin in order to complete his studies at the Academy of Art under the instruction of the sculptor Edwin Scharff. Only after painful struggles with the medium and the models did he return to working without models and combine his own original style with his basic and more profound familiarity with the structure of the human body. He sculpted in stone, two nude female figures, which were critically acclaimed by the Academy of Berlin. When he was forced to leave Germany in April 1933, Ziffer gave one of these sculptures to Albert Einstein, who supported him, both financially and morally, during his three years of study in Berlin. Ziffer's other sculptures remained in Berlin, and their whereabouts are unknown.

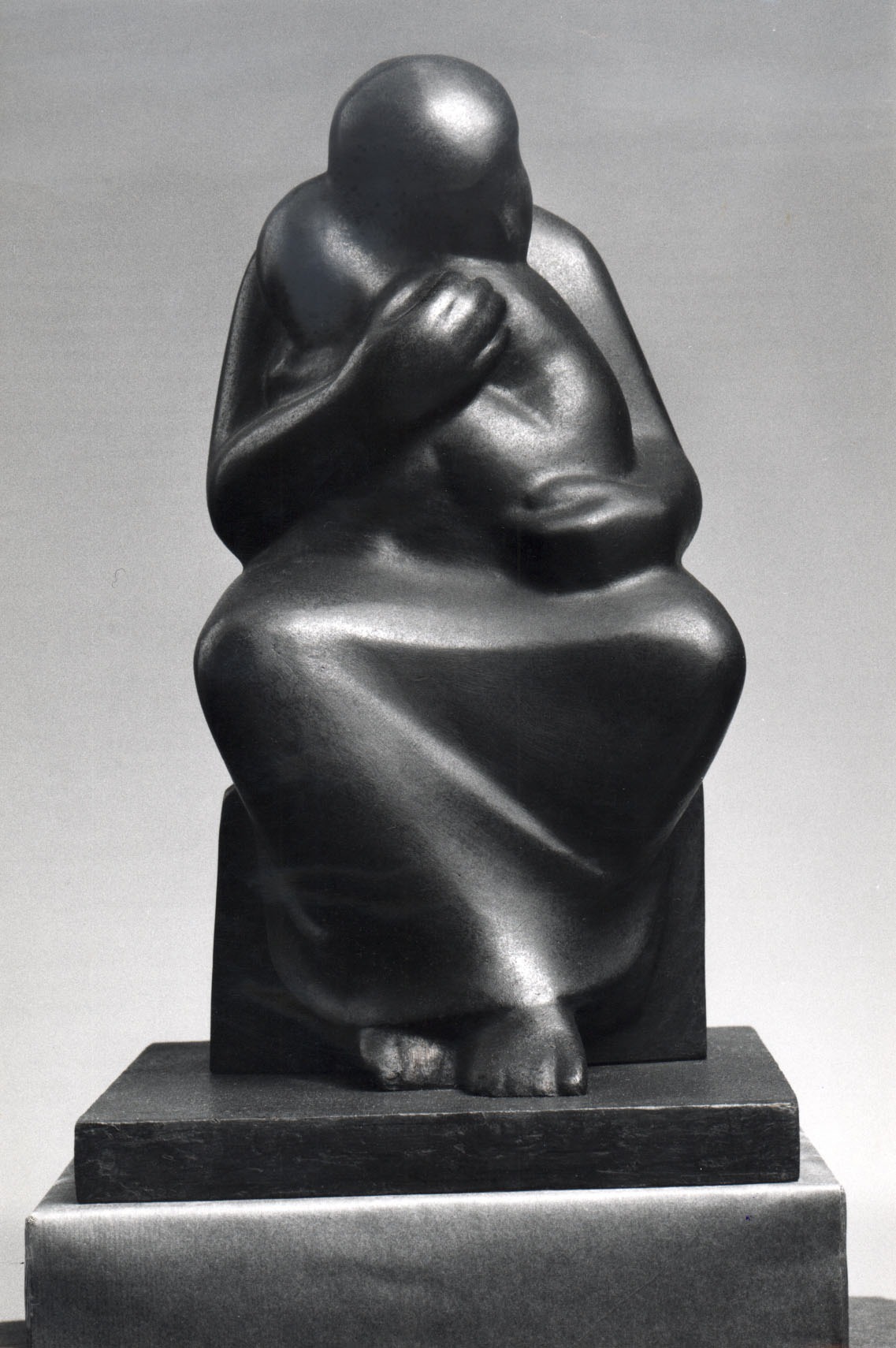

Upon his return to Eretz Israel, Ziffer lived in Jerusalem, where he supported himself by teaching and continued to create decorative sculptures, especially female nudes. He is said to have been influenced by Maillol, but in fact Ziffer met Maillol only after he had established his own personal style, and his affection for Maillol was rooted, rather, in his feeling a closeness to his work. Ziffer himself admitted that because he was not interested in anatomy, he was more able to deal with pure form and to work with greater simplicity. Ionel Jianou rightly points out that contrast to the power, the energy and the monumentalism which characterize Maillol's work, the excellence of Ziffer's female nudes lies in their simplicity and dreamy tranquility, which radiate sensitivity. In 1937 Ziffer again traveled to Paris where he remained until September 1939. During this stay he became acquainted with a number of Jewish painters and sculptors who belonged to the School of Paris and was held in high regard by both artists and critics.

On the eve of the outbreak of World War II, Ziffer returned once more to Eretz Israel and to teaching, first in Jerusalem and then in Tel-Aviv. Over the years he created various large-scale models commissioned for the then Palestine and later Israeli pavilions at international exhibitions (Brussels in 1938, New York in l958); for parks and public buildings (including the Weizman Institute, the Hebrew University and the Haifa Technion); as well as memorial reliefs and monuments throughout the country (Kibbutz Hulda, Netanya, Kibbutz Netzarim and Ain Gedi.

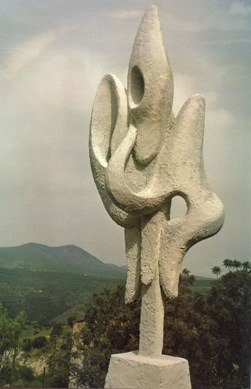

Beginning in 1934, Ziffer paid regular summer visits to Safad, a city he cherished since 1921 when he lived there while to recuperating from malaria. In 1959 he began the restoration of an abandoned l8th century building which included a Turkish bath and which had been given to him by the Safad Municipality. In the large hall of the bath, whose dome rises to a height of 8 m., the artist arranged a permanent retrospective exhibit of his sculptures. With time, he began to tend to the surrounding garden, where he gradually began to display his large sculptures. These had been designed with a view to creating harmony and balance, even by contrast, with the nearby Mt. Meron. Ziffer in this way began using nature as a component in his art. Every sculpture had its own reason for being. Eventually, Ziffer's sculpture garden in Safad became an extensive and unique work, created by the artist from the stone terraces and the surrounding greenery to the sculptures themselves. These sculptures blend harmoniously with the landscape and provide a statement of man's presence amid the wondrous wilderness of the Galilee.

All of the works in the garden are "abstract" in the sense that they do not, in any way, imitate forms and figures that exist in nature. They are self-sufficient forms. In fact, since exhibiting his abstract sculpture ("Keshet" - "Arc" - l954) in the Gan Ha' Em in Haifa, Ziffer ceased to be a figurative sculptor. For him abstract sculpture was a natural return to his beginnings, to the basic problems of plastic form. Simple forms, the play of light and shadow, formal tension based on contrasting directions, which lead to universal harmony - these are the problems that had always occupied Ziffer. "I work with light," he said. "This is my colour." In his works he realized the high ideals absorbed from his Viennese teacher - a complete and perfect synthesis of hand and spirit.

Pictures:

|

|

|

|

| Motherhood, sculpture, Moshe Ziffer, the sculpture garden of Beit Ziffer, Safed |

A sculpture by Moshe Ziffer, the sculpture garden of Beit Ziffer, Safed |